Part 21. Up the Pole.

‘Up the pole’ was commonly used at Oakwood Hospital in 1978 and I don’t think I’ve heard it again since then. Maybe it was peculiar to that hospital or maybe it was swept away in the asylum closure programme of the 1980s. ‘Floridly psychotic’ was the clinical alternative to ‘up the pole’, although it’s a mystery to me how medicine adopted the word ‘florid’. The idea of a botanical psychosis is appealing and if there is such a thing, I hope it’s called Blodeuwedd Syndrome after the character composed of flowers in the Mabinogion. A better alternative to both ‘up the pole’ and ‘floridly psychotic’ is ‘turbulence’, a word preferred by one patient I knew to describe his moments of madness: ‘Brace! Brace!’

According to my Google research, ‘up the pole’ can also mean pregnant, but only in Ireland. At Tooting Bec, a no-nonsense, straight-talking senior nurse rudely greeted news of Eira’s second pregnancy with ‘up the fucking duff again’. Honest at least. By this time we were actively looking for ways to move to Wales, a decision confirmed one Saturday afternoon when a real life ‘up the pole’ event occurred on the Deaf Unit.

To cut a long story short, he had an Andrew Tate type personality, although his faults could be excused by his age (18) and life experience (trauma and a childhood in care). He wore the brittle protective shell suit of a dominant alpha male, spending too much time lifting weights, checking his biceps and trying to wind people up. His communication in sign language was slick and articulate and he easily and often insulted, mocked and ridiculed other patients, using graphic signs and imagery that were surprisingly innovative and grossly offensive. There was nothing pathological about this in a strictly medical sense and indeed it probably fell within the normal limits for a certain subset of adolescent lads. On the other hand, it was certainly debatable whether the Deaf Unit was the right environment for him. Essentially, he represented the disadvantaged side of the more privileged Trump/Johnson/Tory donor coin.

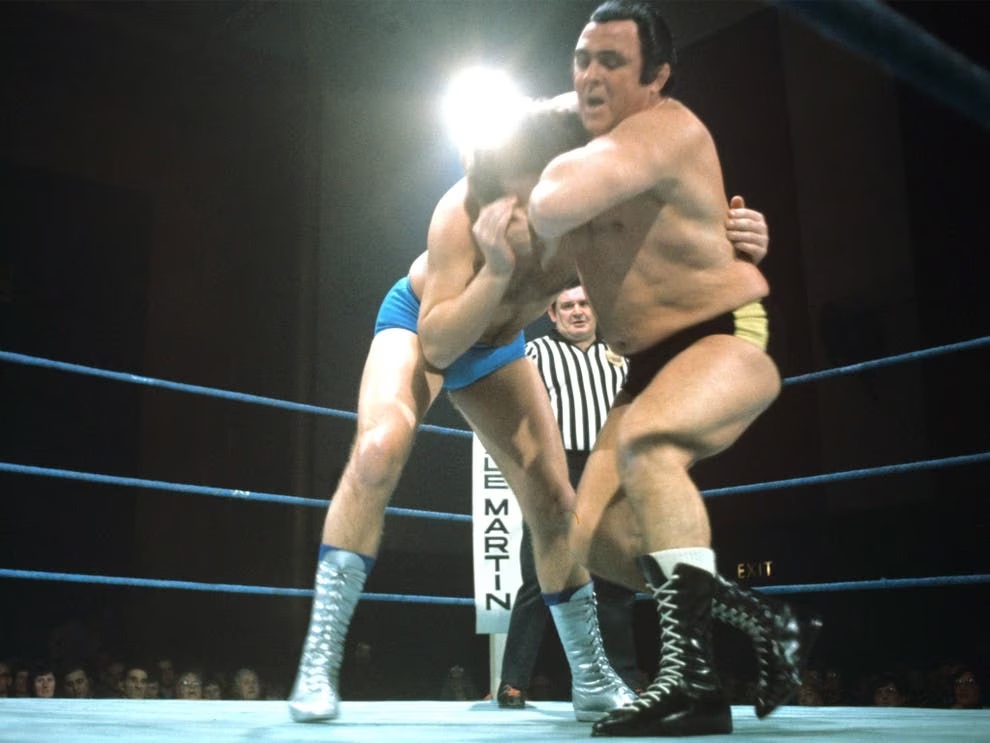

This particular Saturday afternoon I felt compelled to have a word with him about another episode of signed abuse. His response was a well-delivered left hook to my eye, worthy of Henry Cooper in his prime. Luckily I’m not a trained boxer; if I were, I imagine my instinctual response would have been an immediate upper cut followed by instant dismissal. In fact, he instantly dismissed himself by fleeing outside, climbing a telegraph pole and refusing to come down. Following a quick risk assessment (what if he fell? Imagine the paperwork…) I dialled 999. Possibly the first time the Police had been called to Springfield Hospital. These days I understand they are regularly called to acute units around the country. Everything’s gone up the pole.